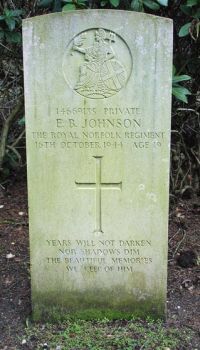

Johnson | Edwin George

- First names

Edwin George

- Age

28

- Date of birth

1916

- Date of death

16-10-1944

- Service number

5771243

- Rank

Private

- Regiment

Royal Norfolk Regiment, 1st Bn.

- Grave number

II. C. 10.

Biography

Edwin George Johnson (Service No. 5771243) was killed in action on 16 October 1944. He was a Private in the 1st Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment. He was initially buried at Cemetery H.J. Hendriks, Overloon and subsequently re-interred on 25 May 1947 in grave II. C. 10 at the Overloon Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in Overloon. His inscription reads “Our loss is great but we hope in Heaven to meet again one we loved so dear.”

Military Career

It isn’t known when Edwin G. Johnson joined the 1st Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment but given that he was born in 1916, it is likely to have been early in the war.

The 1st Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment was still in India on the outbreak of the Second World War. It remained there until July 1940, when it returned home. It then spent the next few years training in Scotland and elsewhere in preparation for what was to come.

It landed in Normandy at Sword Beach on D-Day (6 June 1944). It played its part in the 1st and 2nd Battles for Caen which succeeded on 9 July after which the Battalion had its first rest period since D-Day. It continued the fight in Normandy through mid July and early August and was involved with Operation Goodwood and then in the preparation for the break out from Normandy which succeeded in late August.

From 17 August until 3 September the Battalion had a rest period which also allowed them to take on reinforcements to replace the substantial number of men they had lost. It then moved to Villers en Vexin until 17 September.

By this time, the Allied troops were making a fast advance through France and Belgium to the Escaut canal south of Eindhoven in readiness for Operation Market Garden. On 17 September, airborne troops landed in a corridor from the Belgian/Dutch border via Eindhoven and Nijmegen to Arnhem to secure bridges and allow ground forces to move forward with speed – then to reinforce and strike east into Germany.

The role of the Battalion along with others was to protect the main line of communications northwards along this corridor. It moved on from Villers en Vexin on 18 September and reached Peer on 19 September then Asten on 23 September. They entered Helmond, just east of Eindhoven, on 25 September. It had just been taken by another Battalion and they received an uproarious welcome from the Dutch people.

On 29 September, it moved out of Helmond and on over the River Maas at Grave through Heumen and on to Maldens Vlak. Here they spent time patrolling the area facing the Reichswald Forest in Germany not far to the east. On 9 October the Battalion retraced its steps to Grave, then south to dominate a stretch of the River Maas in the Cuijk area.

Problems with supply lines had resulted in the failure of the Allies to hold the bridge at Arnhem, so plans changed. The Allies found themselves in a narrow salient through the Netherlands and so it was decided to clear the enemy to the south in Overloon, Venray and Venlo while also securing Antwerp to help with supply issues. American troops initially attempted to take Overloon, but did not succeed so the British Army took on the task.

On 11 October, the Battalion therefore moved on foot from Cuijk through Haps and St Hubert and on again the next day to Wanroij, St Anthonis and Oploo, arriving north of Overloon on 13 October. At this time, other British Troops were engaged in capturing Overloon, using an artillery barrage which caused heavy damage to the village.

The Battalion spent the night of 13 October in the woods around Overloon. The ground forward of the woods was flat and featureless and about midway between Overloon and Venray ran a stream called the Molen Beek. From its far bank the enemy had a clear view over a distance of 1000 yards of the British Troops leaving the shelter of the woods.

At 0700 hrs on the morning of 14 October, two companies led the attack to the south with support from two troops of Churchill tanks. The advance was a difficult one, as once through the thick woods there was very little cover. Some tanks were hit and others retreated back into the woods, leaving the Infantry without support. The Battalion succeeded in reaching a point about 400 yds short of the Beek that day, though were left in a very exposed position. They had to remain there the following day while other units reached their positions in order to carry out a co-ordinated attack on the Beek the following day.

The Molen Beek was between 10 and 15 feet wide and had slopping banks about 5 feet high creating an effective gap of about 30 feet. The approaches were difficult with cratered tracks and waterlogged ground. The area was extensively mined. The success of the operation depended on crossing the beek silently by night. Any attempt by day would be suicidal as the road bridge was blown. It was therefore planned that the infantry would cross using floating pontoon bridges while a bridging tank would use a girder bridge for vehicles, including tanks.

The Royal Engineers successfully built the two pontoon bridges overnight – one on each side of the road. At 0500 hrs on 16 October B and D Companies crossed without incident – though it was later discovered that D Company had walked through a minefield of Schumines. Later A Coy did the same with no casualties. By 0600 hrs the leading Companies were keen to press on as they were lying in the open in full view of the enemy and getting casualties. However, other units hadn’t fared as well and so the Norfolks weren’t allowed to push on. The bridging tank failed to lay the bridge under intense fire. On the second attempt a flail tank was half way across when the whole lot toppled into the Beek. The Battalion’s Churchill tanks had all been knocked out – but thankfully the enemy tanks had withdrawn. By 0700 hrs the leading companies were allowed to progress. Casualties mounted up. By the afternoon, A and C Companies were able to push on to about 1000 yds south of the Beek. The Battalion had succeeded in securing the crossing and forcing the enemy to withdraw. This was the day in which Edwin George Johnson and 16 other men of the Battalion were killed.

By 18 October Venray had been taken. Between 13 and 18 October, the Battalion incurred 43 fatal casualties and about 200 wounded.

Family Background

Edwin George Johnson was the son of Charles Frederick and Elizabeth Johnson.

Charles Frederick Johnson had married Elizabeth Sarah Dorey in 1912 in the Wandsworth district of London. Charles was born on 21/4/1892 in Westminster, London while Elizabeth was born on 20/3/1889 in Battersea, London. It is thought that they had children as follows, all born in Battersea, London: Ivy F 1911, Frederick C A 5/5/1913, Edwin G 1914/5, Charles L 10/8/1916, Iris L 27/12/1919, Betty I 14/3/1922, Elizabeth 1924, Ivy F 1927 and Vera in 1932. It is thought that the Ivy F Johnson who was born in 1911 may have died in 1922, aged just 10 and that Elizabeth Johnson may have died in infancy. It is also understood that Betty had a twin who died at birth.

In 1921 Charles and Elizabeth were living with their family at 101, Chatham Street, Battersea. Charles was working as a Platelayer for the Metropolitan District Railway. With them were Ivy, Frederick, Charles (Jnr) and Iris – but not Edwin. Present too was Elizabeth’s sister, Alice E Dorey, born in 1897 in Battersea who was working as a Domestic Servant. At this time, an Edwin G Johnson, born in November 1914 in Battersea, was an inmate of the Joyce Green Hospital and The Orchard Hospital at Dartford, in Kent. This was an isolation hospital which housed patients with smallpox, diphtheria, scarlet fever, measles and whooping cough.

By September 1939, Charles and Elizabeth Johnson were living at 101 Dagnall Street, Battersea. With them were Charles, Iris and Betty – but not the older children Frederick or Edwin or the younger Ivy. Charles (Snr) was working as a Permanent Way Labourer, Charles (Jnr) worked at Hoffman Presser Dryers and Cleaner. Iris was a Labeller at a Paint Manufacturer and Betty was a Filler, also at a Paint Manufacturer.

Frederick had married Rose J Bridger in 1932 in Battersea. In September 1939 they were living at 26 Chesney Street, Battersea. Frederick was working as a Van Driver while Rose was working as a Machine Operator at Arc Lamp Carbons. They appear to have had two children living with them.

It isn’t known where Edwin was at this time. It is possible he may already have been in the army.

Edwin’s sister Iris married Frederick A Powley in Battersea in early 1940 and went on to have one daughter. His sister Betty married Thomas R G Groome in 1942 in Surrey. They went on to have two children.

Edwin George Johnson married Glenys E Horn in late 1943 in the Uxbridge District of Middlesex.

This was Glenys’ second marriage. Her maiden name was Davis and she had married Albert G Horn in September 1938 at St Matthew’s Church, Oakley Square in the Pancras District of London when she was just 19. She had known her husband for 5 years as he was a friend of her brother. Albert was born on 13/9/1913. Glenys was born on 11/9/1919 in Clydach Vale, Glamorganshire, Wales. She was the youngest daughter of William and Margaret Davis. In 1921 she was living with her parents, her brother William Thomas and sister Eliza May at 70, Clydach Road, Blaen Clydach, Rhondda, Glamorganshire. Her father was a Coal Hewer Underground at the Cambrian Colliery Company Ltd. In September 1939 Glenys and Albert were living at 17 Bayham Place, St Pancras, Camden in the same household as George and Ethel Stuckey who where born in 1881 and 1890 respectively. George Stuckey was a Railway ticket Collector and Albert Horn was a Lorry Driver. There was an unnamed record suggesting the presence of a child. However, it is thought that Glenys and Albert only had one child, Kenneth W Horn, born in late 1940 in the Uxbridge District. Albert Horn may have been an early casualty of the war, but this is uncertain.

Edwin’s great niece indicates that Glenys and Edwin had a child, Terence Johnson. However, he knew nothing of his father as his mother remarried.

The family believed that Edwin, who was known as Ted, was a Sergeant in the Army, though this is not reflected in the records of his death. The markings on his uniform sleeve indicate that he was trained in the use of the Lewis Gun. They also understand that he was a prize winning boxer, perhaps during his Army career, and that he also saved someone’s life who fell in the River Thames. They believe that there was a plaque on a London church wall commemorating this rescue, but the church is now demolished.

Aftermath

After Edwin’s death in 1944, Glenys went on to marry for a third time. She married Anthony Del Guidice in the Uxbridge district in 1946. They had a daughter, Glenys E Del Guidice in 1949 in the same district. Glenys Elfreda Del Guidice, born 11/9/1919, died in Hillingdon, Middlesex in 1998.

Edwin’s niece understands that Edwin was reported as “missing in action”. The family heard no more of him and assumed he died in action. His sister Iris used to watch all the news reels at the cinema to see if she could spot him in the background , in the hope that ‘missing in action’ meant he was walking wounded or disoriented. As he never returned they eventually accepted that he was killed, but didn’t know where.

Sources and credits

From FindMyPast website: Civil and Parish Birth, Marriage and Death Records; England Census and 1939 Register Records; Electoral Rolls; Military Records

Information from “Thank God and the Infantry – from D-Day to VE-Day with the 1st Battalion, the Royal Norfolk Regiment” by John Lincoln

History of the 1st Battalion The Royal Norfolk Regiment

Wikipedia Royal Norfolk Regiment

Wikipedia Joyce Green Hospital

St. Pancras Gazette 16 September 1938

Photo and information from Pamela Hill, Edwin’s niece, and her daughter Dawn Everest

Research Elaine Gathercole