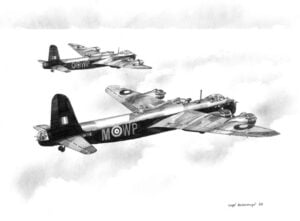

Short Stirling III Serial No. BK 718 with markings WP-M was shot down either by Flak88 or Hayo Hermann (luftwaffepilot) on 4th July, 1943, crashing at Mehlem on the west bank of the Rhine 10 km SSE of Bonn. The crew who were from 90 Squadron were:

Flight Lieutenant Robert Charles Platt (Pilot)

Pilot Officer Andrew Patrick Gilmour (Navigator)

Sergeant Robert Freeland (Air Bomber)

Sergeant Oliver Beard (Wireless Operator)

Pilot Officer Geoffrey Charles Smith (Mid Gunner)

Sergeant Ivor Henry Norris (Rear Gunner)

Sergeant Hugh Murray (Flight Engineer)

The only survivor was Ivor Norris who managed to escape by parachute. He was taken to Germany as a prisoner of war.

With the exception of Hugh Murray, the crew of BK 718 had been together for some time.

Platt and Norris at 16 Operational Training Unit

Ivor Norris’ log book shows that he first flew with Robert Charles Platt on 21st October 1942, while they were both at 16 OTU Upper Heyford. This was an operational training unit which was founded to train night bomber crews. In April 1942 the unit had converted to Vickers Wellington bombers. Between 24th September and 8th November 1942 Ivor Norris was with “B” Flight, flying Wellingtons. He was always shown as a Gunner and flew with a variety of pilots and various aircraft, however it was on 21st October that one of the pilots was a Sgt. Platt. Most of these flights were daytime flights involving bombing, firing rounds and also film reels. Norris switched to “D” Flight on 13th November. From then until 17th December he undertook 17 flights as Rear Gunner, of which 14 were with Sgt Platt as pilot. 12 were by day and 5 by night, with all the night flights being with Platt. Many refer to a “Country Base” in various areas of the south of England and Wales.

By the end of Norris’ time at 16 OTU he had clocked up just over 95 hours of day flying time and nearly 26 hours at night. This includes his initial training at RAF Bridlington from 8th April to 12th June 1942 and his time at 4 Air Gunnery School at Morpeth from 13th June to 23rd September 1942, before his arrival at 16 OTU. At Morpeth, he had flown on the Blackburn Botha aircraft and qualified as an Air Gunner on 25th July 1942. From then until he left Morpeth he seems to have been acting as an instructor.

Platt, Norris and Smith at 1657 Conversion Unit

He was transferred to 1657 Conversion Unit at RAF Stradishall, Suffolk, on 7th January 1943. The purpose of this unit was to convert pilots who were initially trained on medium bombers to flying heavy bombers such as the Stirling Bombers. The Short Stirling was a British four-engined heavy bomber which was the first four-engined bomber to be introduced into service with the RAF. Ivor made 14 flights at this unit between 18th January and 20th February 1943 of which 4 were night flights. With a couple of exceptions, he again always flew with Sgt. Platt as the pilot and they flew a variety of different Stirlings, with Ivor always shown as Rear Gunner. They were generally doing what is shown as “Circuits and bumps”, together with shooting film reels. Norris clocked up a further 19:30 hrs day flying and 6 hrs night flying.

Geoffrey Charles Smith had arrived at 1657 Conversion Unit on 2nd January 1943, around the same time as Norris. Smith had joined up in the RAF Volunteer Reserve on 12th March, 1942 at the St John’s Wood Air Crew Reception Centre and was assigned to the Air Crew Dispersal Wing on 4th April 1942, just a few days before his 19th birthday. He was assigned to 81 Squadron Training Wing from 15th May to 2nd September 1942. This was initially based at Hornchurch in Essex but moved to nearby Fairlop in July. He was then transferred to 14 Initial Training Wing in Bridlington, Yorkshire on 19th September. This undertook initial service training for air gunners. He was there for just over a month before transferring to No. 9 Observers Advanced Flying Unit at RAF Penrhos in Wales on 25th October. He was again transferred in less than a month, this time to 1483 Flight at RAF Marham in Norfolk. This was a Gunnery Flight. On 18th December he was transferred to 115 Squadron at RAF East Wreatham in Norfolk which was a Bomber Squadron. He then arrived at 1657 Conversion Unit on 2nd January 1943. Only the pilot’s name is given in Norris’ log book – so it isn’t known whether Smith became part of Platt’s crew at that time or not.

The Crew except Murray at 90 Squadron

Norris moved on from 1657 Conversion Unit on 20th February 1943 to 90 Squadron but his first flight for this Squadron did not take place until 3rd March. Smith was also transferred to 90 Squadron on 22nd February 1943. On 28th February Sgt RC Platt was noted as a Pilot in “B” Squadron.

90 Squadron, which was under Bomber Command, had been re-formed at Bottesford, Nottinghamshire on November 7th 1942. It moved to Ridgewell on the Norfolk / Cambridgeshire border on December 29th that year and subsequently spent five months there (then a satellite of Stradishall), only to be moved on again when Ridgewell was required for use by the USAAF’s 381st Bombardment Group. 90 Squadron flew the first of the four engined heavy bombers, the Short Stirling. This was the least effective of the three British heavy bombers, but 90 Squadron had to soldier on with this type until June 1944. 90 Squadron was the first squadron to be based at Wratting Common, then known as West Wickham. An advance party made the short journey from Ridgewell on 30 May 1943, and the main party and the Squadron’s Stirling aircraft arrived next day. 90 Squadron flew the first of the four engined heavy bombers, the Short Stirling. This was the least effective of the three British heavy bombers, but 90 Squadron had to soldier on with this type until June 1944.

Norris undertook four non-operational flights from 3rd to 9th March, of which two had Platt as pilot and two did not. His first operational flight was on 11th March and was a mine laying operation near the Frisian Islands. The crew on this flight was as follows:

Sgt Robert Charles Platt (Pilot)

Sgt Andrew Patrick Gilmour (Navigator)

Sgt Robert Freeland (Air Bomber)

Sgt Oliver Beard (Wireless Operator)

Sgt Geoffrey Charles Smith (Mid Gunner)

Sgt Ivor Henry Norris (Rear Gunner)

Sgt A.N Birkinhead (Flight Engineer)

None of this crew were recorded on 90 Squadron operational flights prior to 3rd March, suggesting they had all just arrived in 90 Squadron. Little is currently known of the service history of the rest of this crew except for that already described for Platt, Smith and Norris. All that is known is that Robert Freeland had joined up in Edinburgh in September 1941 and had been trained in South Africa.

From 11th March onwards Norris flew exclusively with Robert Charles Platt as Pilot on both operational and non operational flights. In his time with 90 Squadron Norris flew a total of 57 flights and clocked up 48:55 day flying hours and 97:50 night flying hours, with most of the latter being operational. This took his total flying hours to 163:30 by day and 129:35 by night.

From 11th March until 20th April their flights were generally in Stirling 1 “O” EF 349. Their first operational flight was in this plane on 11th March. However, on 23rd April they did an air test in Stirling “M” BK 718. This had arrived from Birmingham on 13th April. Their first operational flight in this plane was on 26th April and they continued to use it for all but one operational and most non operational flights from then onwards.

Non operational flights were generally during the day. The purpose of these was very often described as “Air Tests”, sometimes on different aircraft. Other purposes included loaded climbs, formation flying, group bombing exercises, night flying tests (though these occurred in daytime), compass swing tests and a bombing competition. On 30th May 1943, a 30 minute flight was made at 16:00 hrs to West Wickham. It was around this time that 90 Squadron moved from RAF Ridgewell to RAF West Wikham, also known as Wratting Common.

Operational Flights

Platt and Norris flew a total of 18 operational flights in 90 squadron. The crew was almost always the same on these operational flights as that on 11th March. Sgt RFW Porteous took Robert Freeland’s place on 14th April and Sgt WJ Hope took Geoffrey Smith’s place on 13th May, though Freeland and Smith returned for the next flight. The Flight Engineer, Sgt A.N. Birkinhead was not present on either the 19th or 21st June which were the last two flights before the fatal flight on 3rd July. On the 19th he was replaced by F/Lt R Holmes; on 21st he was replaced by Sgt J Williams. Also, on five occasions they flew with a second pilot on board. It is presumed that the same regular crew flew in the non operational flights as well.

The crew all started out as sergeants on 11th March 1943. Platt was shown as a Pilot Officer the following day; as a Flight Sergeant on 19th June and Flight Lieutenant on 21st June. Gilmour was shown as a Flight Sergeant on 26thApril and a Pilot Officer by the time of his final flight.

The following is the list of operational flights undertaken by this crew while in 90 Squadron. All were night flights. Also shown are the number of aircraft deployed by 90 squadron on that attack and the number who aborted and those which failed to return:

On only one of these occasions did the crew fail to deliver its objective. On the flight on 8th April it returned early after less than an hour owing to high oil temperature and low oil pressure in the starboard inner engine. The bombs were jettisoned safely 5 miles south of Ridgewell from 2,500 feet. As can be seen it was not unusual for flights to be aborted in this way. Neither was it unusual to lose aircraft. On 60 operational missions involving 514 flights by 90 squadron between 8th January and 28th June 1943, 52 aircraft had to abort while 27 failed to return and 2 crashed in the UK. There were numerous other occasions where missions had to be cancelled due to bad weather.

Mine Laying operations were cryptically described as “Gardening” and the mines as “vegetables”. The Frisian Islands were described as “Nectarines” and Keil Bay as “Quince”. So, for example, on the 11th March the crew were “Detailed to plant vegetables at Nectarines I and planted 6 x B200”. They make specific reference to checking their location by sighting two of the Frisian Islands – Ameland and Terschelling. On 28th April they planted in Quince N as ordered. Visibility was good and they could see the north end of Langeland. Other crews reported slight help from the Northern Lights. The crew suffered some damage by flak from Langeland after dropping their load and the contents of No. 4 tank was lost but they got back to base.

In the bombing operations they were dropping substantial numbers of bombs and incendiary devices on markers and noting the extent to which they saw resultant fires or explosions on the ground. Sometimes they also tried or succeeded in taking photos. The 4th April was the first time 90 Squadron had attacked Keil. The crew attacked as ordered at 23:14 hours dropping 80 x 30 lbs. incendiaries, 918 x 4 lbs incendiaries and 612 x 4lbs “X” from 12,000 feet. Visibility was good and fires could be seen where red and green markers had been seen previously. On the attack on Stuttgart on 14th April the crew bombed the green markers and believed that they fell on the railway yard. The Heinkel works at Rostock was the target on 20th April. On the attack on Duisburg on 12th May the crew described it as a well concentrated attack. One particularly large fire developed into a large explosion and the glow could be seen from the Dutch coast on return. On the attack on Dortmund on 23rd May they noted that the bombs fell in a built up area. On 29th May on the attack on Wuppertal they dropped what was described as “96 x 30, 918 x 4 and 162 4”X” incendiaries. They also mention dropping two packages of “G32A” in the area and attempting to take one photo. The marking of targets seems less effective than on other missions – but they reported seeing a big oil fire with smoke rising to 6000 ft.

It seems that the crew sometimes had a break from flying. Ivor Norris’ logbook shows he made no flights at all between 12th March and 3rd April. The squadron itself had no operational flights from 12th to 27th March due to bad weather and although the squadron recommenced operational missions on the 27th this crew did not fly on a mission again until 4th April. Norris, and presumably the rest of the crew, had another break from flying between 28th April and 11th May and on 4th May BK 718 was flown by a different crew. A different crew also flew BK 718 on 25th May and 3rd June. From 3rd June to 19th June there was little activity for the Squadron as a whole. The squadron returned to flying operational missions on the 19th June. This crew took part in that and the mission on 21st June, though without their usual flight engineer. The operation on 21st June was their last operational mission before the fatal crash. Norris’ log book indicates that they did not fly at all between 22nd June and the morning of 3rd July although the Squadron flew 5 further operational missions in that period, suggesting that this crew had another break.

Murray Replaces Birkinhead for the Fatal Flight

On 3rd July 1943 Stirling “M” BK718 took off at 11am for a night flying test with Flight Lieutenant Platt as the pilot and Sgt. Norris as the rear gunner. However, Flight Engineer Hugh Murray replaced Flight Engineer A. Birkinhead on this flight. They landed safely after a 30 minute flight.

Hugh Murray had worked as a mechanic at the Lochgelly garage of Messrs Alexander & son Ltd – a bus company. He joined the RAF in January 1939, before the war, so in that respect differed from the rest of the crew who had all joined via the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve after the war started.

It is possible that in the early years of his service, Hugh was using his technical engineering skills as RAF ground crew. However, Flight Engineers were introduced into the RAF in 1941. Their primary role was to assist pilots in the flying of large, multi-engine aircraft such as the Short Stirling that had become too technically complex to be operated by a single pilot. By taking over management of the aircraft’s various system the Flight Engineer released the pilot to concentrate on the actual flying of the aircraft. The Flight Engineers had specific technical training on each aircraft, sometimes spending time with the aircraft manufacturers. Their role could require them to make temporary repairs in flight if the aircraft was damaged. They also took a three-week gunnery course as part of their training in order that they might take over a turret or gun if an Air Gunner were to be killed or wounded. At this time too it was no longer required to have two pilots for heavy bombers as the Flight Engineer could also act as a second pilot. Also, to ensure that all aircrew received reasonable treatment from the enemy should they fall into their hands as prisoners-of-war, a minimum aircrew rank of Sergeant had been established.

Hugh’s Flying Log Book shows that he qualified as Flight Engineer on the 12th October 1942 as a Corporal, subsequently amended to Sergeant. His flying record started on 9th Dec 1942 when at 1651 Conversion Unit based at RAF Waterbeach, 6 miles N of Cambridge. The role of 1651 Conversion Unit, like 1657 Conversion Unit was to convert aircrews to the heavy bombers such as the Short Stirlings. He completed 29 flights as Flight Engineer on a variety of Stirlings – a total of 40h 10m flying time of which 11h 5m was at night. Most were with Sgt Southall as pilot. They initially included a lot of circuits and landings during the day then laterally more cross country night including bombing practice. Hugh remained there until 21st January 1943.

He then transferred to 149 Squadron at RAF Lakenheath, flying Short Stirling 1 bombers. This squadron was part of Bomber Command. His Log Book shows flights there from 6th February to 11th March 1943. During this time, he carried out 11 flights in a variety of Stirlings – a total of 29h 15m flying time. In all but one he was the Engineer with Sgt Southall as Pilot (promoted to Pilot Officer from 13th February). These included 4 operational night flights out of the 12 undertaken by the squadron during this period. This limited number, together with the fact that different planes were used, suggests that perhaps this crew was being used as a relief crew for other, more regular crews. In addition to Hugh Murray, the crew for these was: Pilot Officer GTP Southall as Captain, Sgt DA Nicol as Navigator, Sgt JK Dawes as Wireless Operator, Pilot Officer GP Read as Mid Upper Gunner, Pilot Officer RR Clifton as Bomb Aimer and Sgt H I Stott as Air Gunner. Only the flight to Wilhelmshaven on 19th February was entirely successful. The flight to Lorient on 16th February had to return early due to problems with the rear turret; that to Essen on 5th March also returned early and that to Nuremburg on 8th March crash landed at Leavenheath in Suffolk, but with no casualties. The non operational flights included air tests, load climbing tests and bombing practice.

The first Stirling III flew in an operational mission at 149 Squadron on 25th February and by May the Stirling IIIs were more prevalent there than the Stirling Is. Sometime after 11th March Murray joined 1657 Conversion Unit at RAF Stradishall and remained there until 22nd April 1943. This may have been to train him on Stirling IIIs. Between 12th and 22nd April he undertook 16 flights amounting to 34h 35m flying time on various Stirlings but usually with Flight Sergeant Hyder as Pilot. These started largely as daytime circuits and landings during the day then latterly at night.

He had returned to 149 Squadron by 29th April and remained there until 11th June. He carried out 22 flights (48h 40m), all as Engineer and all until the last three in June with Flight Sergeant LA Hyder as pilot. They used various planes initially, but from 13th May they used Stirling III BF 477 “D” almost exclusively. They carried out four operational flights in this time as well as one air / sea rescue. Again, this seems a small number compared to the 21 operational flights by the squadron in this period. They included mine laying near Bordeaux on two occasions and bombing at Bochum on 13th May and Dortmund on 23rd May. The latter two again had problems with a useless starboard inner engine on the first and a fire in the outer engine on the second causing them to have to land at Hardwick. Apart from the fact that Flight Sergeant Hyder had replaced Pilot Officer Southall as Pilot, the rest of the crew was usually the same as he flew with earlier in the year. Non-operational flights included air tests and a variety of other practice routines.

By 22nd June he was again at 1657 Conversion Unit but only carried out 3 flights between then and 24th June. By this point he had undertaken 86h 15m of daytime flying and the same number of night flying hours.

The Fatal Flight

It seems that shortly after this date he transferred to 90 Squadron, based at West Wickham. The next two entries in his Log Book are on 3rd July, 1943 – the final entries. The Pilot was Flight Lieutenant Platt. He joined Platt’s crew on BK 718 for the test flight at 1100. The same aircraft and crew took off again at 2326 hours from West Wickham. It was a night time raid with just a 2% moon. The target was the Cologne region on the east bank of the Rhine where most of the industry was located. In total, this operation involved 653 aircraft with 30 losses (4.6%). Accurate ground marking by Oboe equipped Mosquitoes led to another very significant blow to this Ruhr city. 20 industrial premises and 2200 homes were completely destroyed and 588 people killed. A further 72,000 people were bombed out. This was the first time the ‘Wild Boar’ technique had been used, in which the flak height was limited to allow night-fighters to fly over the main force and pick out aircraft in silhouette against the fires below.

However, there were 30 losses, including the BK 718 which crashed near Mehlem on the west bank of the Rhine, 10 kilometers south-east of Bonn in Germany. Six of the crew were killed but Flight Sergeant Ivor Norris was able to bail out and landed safely by parachute. He was taken as a Prisoner of War. The crew is buried at Overloon War Cemetery in The Netherlands.

It is interesting to note that there is also a POW record for Andrew Patrick Gilmour – but this still shows his date of death as 4th July, 1943. It is possible that he may have still been alive after the crash and was captured but died later that same day.

Sources and Credits

International Bomber Command Centre Losses Database

Ivor Norris’ Logbook – from his son Tony Norris

Other information on 90 squadron missions and crew collected by Ivor Norris – from Tony Norris

Hugh Murray’s Logbook from his nephew Hugh Murray

90 Squadron Operations Record Books Feb-Jun 1943: National Archives AIR 27/731 10, 12, 14, 16, 18

90 Squadron Operations Summary Feb-Jun 1943: National Archives AIR 27/731 9, 11, 13, 15, 17

149 Squadron Operations Record Books Dec 1942: National Archives AIR 27/1002 24

149 Squadron Operations Record Books Jan -June 1943: National Archives AIR 27/1003 2,4,6,8,10,12

Assistance from Dick Breedijk – National Archives – Operational Records for BK718

Geoffrey Charles Smith’s Service Record from the Ministry of Defence

National Archives WO 416/139/204 – Andrew Patrick Gilmour POW Card.

Various RAF related websites for information on RAF units

Royal Air Force Flight Engineer & Air Engineer Association Website

Drawings made and donated by Ivan Berryman

Research by Elaine Gathercole, Tracey van Oeffelen and Gerard Berkers